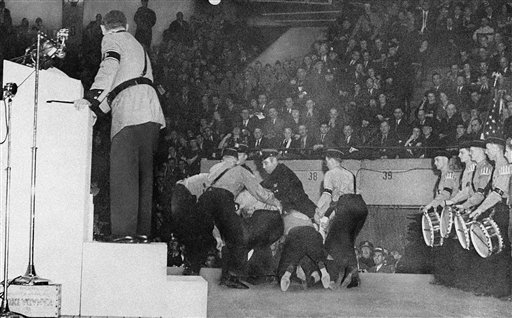

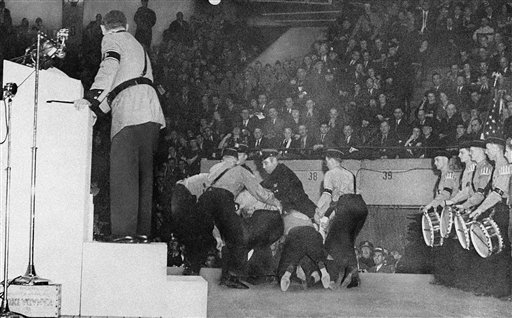

A heckler’s veto occurs when the government accepts restrictions on speech because of the anticipated or actual reactions of opponents of the speech. Heckler's vetoes have been typically struck down by the Court. In this photo, a literal heckler is apprehended on the platform at New York’s Madison Square Garden in 1939. Fritz Kuhn, National Bund leader, stands on the rostrum, his back turned as he regards the struggle which interrupted his Denunciation of Jews during a stormy Bund rally. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

A heckler’s veto occurs when the government accepts restrictions on speech because of the anticipated or actual reactions of opponents of the speech. The Supreme Court first recognized the term in Brown v. Louisiana (1966), citing the work of First Amendment expert Harry Kalven Jr., who coined the phrase. The term is also used in general conversation to refer to any incident in which opponents block speech by direct action or by “shouting down” a speaker through protest.

Although some scholars make reference to a string of heckler’s veto cases, the idea appears across a wide range of cases in First Amendment law as a label critical for any claim, made in defense of the government’s suppression, that speech inciting hostile reactions may be restrained.

The offense to audiences and their reactions to expression generally have been important justifications for restrictions on speech. Issues of obscenity and “fighting words” are common examples. The circumstances that raise a heckler’s veto, in which the claim of offense has been viewed with much greater skepticism, can be distinguished in two ways. First, speech protected by raising the heckler’s veto objection is considered to have some value or contribution to public debate, unlike the forms of speech that the Supreme Court has left categorically unprotected. Second, cases involving supposed hecklers’ vetoes usually concern the behavior of crowds, not an impressionable observer or an individual who might be provoked to fight.

A heckler’s veto “doctrine” has sometimes been articulated as the principle that the Constitution requires the government to control the crowd in order to defend the communication of ideas, rather than to suppress the speech. Yet the larger the opposition grows and the more difficult it is for the government to protect the speaker, the more compelling become the practical considerations in restricting or removing the speaker from the scene.

The landmark heckler’s veto case is Terminiello v. Chicago (1949), in which a riot took place outside an auditorium before, during, and after a controversial speech. Justice William O. Douglas, writing for a 5-4 majority, held unconstitutional Arthur Terminiello’s conviction for causing a breach of the peace, noting that speech fulfills “its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger.”

Just two years later, in Feiner v. New York (1951), the Court nevertheless upheld Irving Feiner’s conviction for causing a breach of the peace, in similar circumstances, after the police asked him three times to stop speaking to a crowd that was growing hostile.

In general, the core concern with the heckler’s veto is that allowing the suppression of speech because of the discontent of the opponents provides the perverse incentive for opponents to threaten violence rather than to meet ideas with more speech. Thus the Supreme Court has tended to protect the rights of speakers against such opposition in these cases, effectively finding hecklers’ vetoes inconsistent with the First Amendment.

This article was originally published in 2009. Patrick Schmidt a Professor of Political Science and Co-Director of Legal Studies at Macalester College. He writes and teaches in U.S. constitutional law and judicial politics.