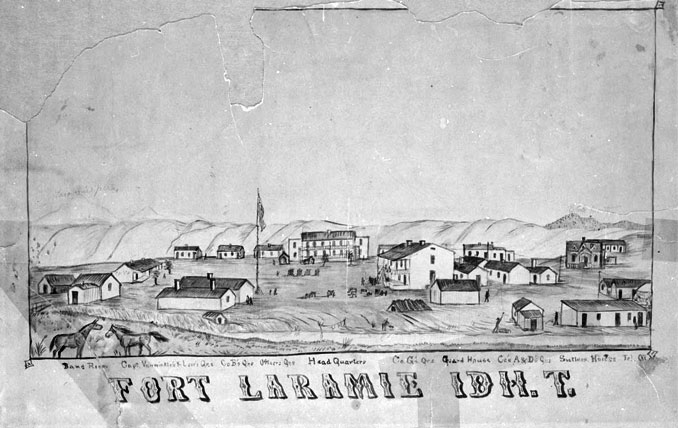

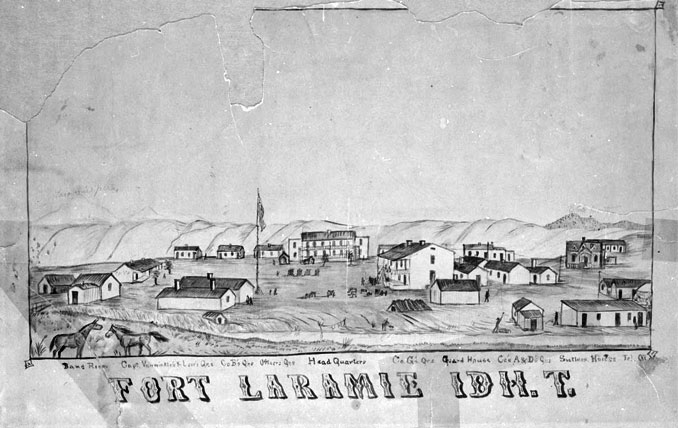

Toward sunset one evening in March 1866, a large group of Indian, white and mixed-blood people moved away from the parade ground at Fort Laramie and out toward a graveyard on a hill. Leading them was an army wagon with a coffin in it. Next came a small group of relatives of the dead girl. Their clothes, a feather or two, and the fur around the edges of their buffalo robes fluttered slightly in the breeze. Next came a large crowd of officers, enlisted soldiers, and tribespeople, walking quietly and paying attention to the weather and their steps. Slowly they made their way over the ground past the sutler’s store and hospital, and up a low rise beyond.

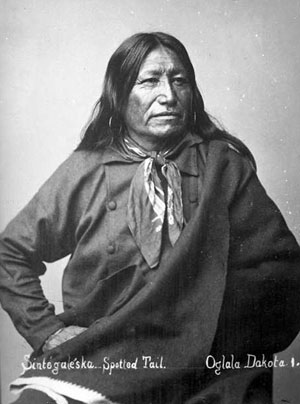

At the cemetery was a platform on four posts about seven feet high. The relatives of the dead girl gathered closest around the coffin: her mother, her aunts, and her father, Spotted Tail or Sinte Gleska, chief of the Brulé or Sicangu Lakota, called Sioux by the whites. The other Indians and soldiers stood in rings around the relatives.

|

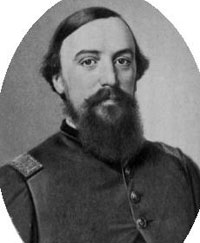

Then in the silence a chaplain gave a prayer, which an interpreter translated into Lakota. The dead girl’s mother and aunts wept quietly. Other people placed special things on the coffin. Col. Henry Maynadier, the highest-ranking soldier at the fort, laid down his best kid gloves. Then the girl’s relatives covered the coffin with a buffalo robe and a red wool blanket, raised it to the platform, and tied it down with leather thongs.

By 1866 war between Indians and whites had become almost constant on the high plains of what soon would become Wyoming. An event like this was rare. Old-timers regarded it as “unprecedented,” Col. Maynadier reported to officials back in Washington, D.C. But he had high hopes, he added, that the mutual feelings of loss would allow both sides to come together in “a certain and lasting peace.”

Young Mni Akuwin

Spotted Tail’s daughter Mni Akuwin—Brings Water Home—was born about 1848, so she would have been 17 or 18 when she died. Probably she was with her people when trouble broke out in their village in 1854, and 2nd Lt. John Grattan and his 30 soldiers were killed, and with her people also when they were attacked in turn by Brig. Gen. William Harney’s cavalry on Blue Water Creek in western Nebraska the following year. Many children and women were killed in that fight, and many more were taken back to Fort Laramie by the soldiers, as hostages.

When her father went to prison at Fort Leavenworth in distant northeastern Kansas the year after that, his family went with him. On their way home, after he was released, they spent some months at Fort Kearny in Nebraska. And each year after that, when Spotted Tail and the Brulé people visited Fort Laramie to trade and to pick up the food and clothes the government had promised them, Mni Akuwin went along.

She became a particular friend of the officers and their wives—“they made a pet of her,” one historian put it. She loved to watch soldiers march and turn and slap their rifles to the ground. And they liked showing off for her. “Among ourselves we called her ‘the princess,’” an officer remembered many years later. “She was looking, always looking, as if she were feeding upon what she saw.”

Years of war

Relations worsened between whites and Indians as tens of thousands of people poured each year past Fort Laramie on the Oregon/California/Mormon Trail. The Brulé people stayed more friendly than other Lakota bands did—the Oglala and the Hunkpapa, for example. But after the massacre of a peaceful Cheyenne village on Sand Creek in Colorado near the end of 1864, even the Brulé felt they had to make war. That winter, the southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, and various Lakota bands all moved north, raiding as they went. On the Powder and Tongue Rivers in northern Wyoming, they joined up with the Oglala, in gatherings of great power.

The following summer was all-out war. Lt. Caspar Collins and 26 other soldiers were killed in a fight at what’s now Casper, Wyo. General Patrick Connor led a successful attack on an Arapaho village on the Tongue River, but his 2,500 troops came close to starving later that summer as they chased the tribes all over the Powder River country. From Fort Laramie, Col. Thomas Moonlight sent Spotted Tail and the Brulé under guard down the Platte to Fort Kearny, as prisoners of war. But they escaped, crossed the river, and headed north. When the cavalry came after them the Indians ran off all the soldiers’ horses, and they had to walk 100 miles back to Fort Laramie in disgrace, carrying their saddles.

The whites realized they were getting nowhere, and decided to see if they could make peace. In the fall, Col. Maynadier sent messages out to the Oglala and Brulé bands in the Powder River country. After three months the messengers returned: Red Cloud and 250 Oglala lodges would come the fort to talk, also Swift Bear, Spotted Tail, and the Brulé people. Despite their victories, it had been a hard winter. Buffalo were harder than ever to find, and when the generally peaceful tribes like the Brulé made war, they had to do without the yearly supplies the government owed them otherwise.

Just as the Brulé were starting on the long trip south to Fort Laramie, Mni Akuwin died, probably of tuberculosis or pneumonia, perhaps of simple hunger and exhaustion. She had never done well away from the forts. Before she died she asked her father to have her buried near the fort. Spotted Tail sent a message to Maynadier asking if this would be possible. Maynadier immediately answered yes.

The colonel had known the family years before, perhaps when he spent the winter on Deer Creek near what’s now Glenrock, Wyo., with an army expedition mapping parts of what are now Wyoming and Montana drained by the Yellowstone River. But up to this point Maynadier had been unsure of Spotted Tail’s real intentions—whether peaceful or warlike. Now he was sure the chief meant peace. He rode out with a small group of officers to welcome the Brulé when he learned they were near.

Back at the fort, Maynadier told Spotted Tail that a special commission of peacemakers would arrive from the East in a few months to work out details of a treaty. Meanwhile, he was honored that the chief would trust him with his daughter’s remains, and they should have a funeral at sunset.

Spotted Tail was moved, yet calmed by the colonel’s sympathy. He said the tribes were due payments to make up for the vanishing buffalo, and all the new roads being built through their lands. But such matters could wait for later, he said, when the peace commissioners came. The chief’s emotions had a strong effect on the other Indians, Maynadier reported, “and satisfied some [whites] who had never before seemed to believe it, that an Indian had a human heart to work on and was not a wild animal.”

An attempt at peace

Within a few days, Red Cloud and 200 Oglala warriors arrived. As weeks went by, more and more Indians camped nearby, coming and going all the time. The soldiers were nervous, especially when the Indian men walked around with their bows strung and their hands full of arrows. The soldiers didn’t trust their officers, either. Private Hervey Johnson wrote home to his sisters in Ohio that Maynadier had been making nothing but promises to the Indians all spring, “the most of which he is unable to fulfil, and in fact being drunk most of his time I guess he don’t know half the time what he is promising.”

Johnson was right. Maynadier was making a lot of promises, and giving out a lot of presents and supplies so the tribes would stick around. This was risky. Though it was clear the grieving Spotted Tail was for peace, neither Maynadier nor any of the white officers had bothered to find out what Red Cloud and the Oglalas thought.

At last the peace commissioners arrived. The government had no desire, they told the Indians, to buy or occupy their land. All they wanted was a safe way through the Powder River country. Gold had been discovered in Montana, and much of the fighting had been along the Bozeman Road, the new road north to the gold fields. Whites would stay on the roads and wouldn’t kill off the buffalo or otherwise disturb the game, the commissioners promised. If the tribes would agree, they would be paid well in yearly supplies. Red Cloud and Spotted Tail asked for time to bring in the rest of their people, camped in Nebraska, a few days’ journey away.

The day the peace talks reopened, by sheer coincidence, Col. Henry B. Carrington and 700 troops showed up at Fort Laramie. They were on their way to build new forts on the Bozeman Road. No one had told the Indians about this. Red Cloud was disgusted. Here the Indians had agreed to nothing, and yet the whites were sending a new army to build new forts in the country they still had no rights to travel through. With the other fighting Indians, mostly Oglala, he left and went back north.

Spotted Tail, the Brulé people and some southern Oglala people signed the treaty. They were tired of war, tired of living away from the big forts, and they had never really regarded the Powder River country as theirs in any case. The commissioners had signatures on paper, but their loose promises and the army’s bad timing only ensured more war.

More war

It came to be called Red Cloud’s War. Carrington’s troops strengthened Fort Reno on the Powder and built two more forts—Fort Fort Phil Kearny on Piney Creek near what’s now Story, Wyo., and Fort C.F. Smith on the Bighorn River in Montana Territory. The tribes raided the road constantly, making travel almost impossible. In December, Red Cloud’s Oglala warriors and their Cheyenne allies lured Captain William Fetterman and 80 soldiers out of Fort Phil Kearny and killed them all in the snow. Two more fights near the forts the following summer ended in a draw.

Again, the government was ready to try peace. But this time, the Union Pacific Railroad was being built across the plains, changing everything. After the Indians made just a few raids on the railroad route, company officials had threatened to stop work altogether unless the government could protect the crews.

Congress appointed a new peace commission in 1867. These men met first with leaders of the southern plains tribes in Kansas—Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche and Apache. The leaders agreed their people would move onto reservations. But the people didn’t like the idea much, and soon rejected it. At Fort Laramie, no Lakota people would come in to talk at all. Red Cloud sent word that the war would stop as soon as the army abandoned the new forts and closed the Bozeman Road.

Peace again on the horizon

And this, the government was ready to do. For one thing, the army had shrunk drastically since the end of the Civil War. There simply weren’t enough troops to protect the Bozeman Road, the railroad builders and the new black citizens and their right to vote in the Reconstruction South.

Second, war was expensive. Congressmen who favored peace argued it was cheaper to feed the Indians than to fight them. Third, it was unjust. Ever since Sand Creek, Congress and the nation had been rethinking the fairness of making war on Indians to force them to give up their lands.

Finally, as soon as the new railroad was finished, there would be a much shorter wagon route north from Utah to the gold fields of western Montana. Whites would not need the Bozeman Road anymore. It wasn’t worth more war.

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant sent word to abandon the forts on the Bozeman Road. The peace commission took the train to Cheyenne in early April 1868, and from there took the road to Fort Laramie. With them they brought Spotted Tail and his headmen from Nebraska, and a load of presents for any Indians willing to sign a new treaty.

A new treaty, an uncertain future

The Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868, as it came to be called, set aside a reservation for the Lakota that included all of what is now South Dakota west of the Missouri River. This was a lot of land, but not nearly as much had been set aside for the Lakota in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, seventeen years before. The new treaty also allowed the Lakota to keep hunting on what was called “unceded Indian territory.”

This included the Powder River country the Oglala had fought so hard to keep—all the land north of the North Platte and east of the Bighorn Mountains. It also included land south of the South Platte along the Republican River in Kansas and Nebraska, which was meant for Spotted Tail’s Brulé people.

But most of the words in the treaty are about farming—how the Indians could file land claims on the new reservation, how they could eventually own the land as individuals, separate from their tribes, how owning land would allow them to be full U.S. citizens, how the government would provide them with seeds, tools, and oxen to pull their plows, and provide them too with expert farmers to advise them, blacksmiths to fix their tools, millers to grind their grain, and teachers to teach their children an English-language education.

Many Indians, including various Brulé, Oglala, Minniconjou, and Yankton Lakota people, plus some Arapaho people, signed in April and May, but all who did so had been more or less friendly already. The army finally abandoned Fort C.F. Smith on July 29. Red Cloud and his warriors burned it down the next day, and burned Fort Phil Kearny after it and Fort Reno were abandoned a few days later. Red Cloud sent word he might come in after a while, but first, the Oglalas would go hunt buffalo, as they did every fall.

On November 4, Red Cloud came to Fort Laramie. With him were about 125 men, leaders of the Oglala, Hunkpapa, Brulé, Blackfeet, and Sans Arc bands of the Lakota. The peace commissioners had all left months before, Maynadier was no longer in charge, and only Col. William Dye was on hand at the fort to take their signatures.

When Dye was explaining the complicated parts of the treaty about land claims and farming, Red Cloud interrupted. His people were not interested in leaving their country for a new place, or in farming, he said. He added that he had not come because he’d been sent for, but only to hear the latest news, and to get some ammunition for fighting the Oglala’s old enemies, the Crow. Dye said he couldn’t provide powder and lead for any Indians still at war with the U.S. The next day, Red Cloud had more questions, especially about how far the hunting grounds and reservation actually extended. It seemed as if the talks would bog down in detail and suspicion.

Finally, nervous and reluctant, Red Cloud rubbed his hands in dust from the floor, washed them with a dusty washing motion, took a pen, and made his mark on the treaty paper. He asked all the white men to touch the pen, which they did. Then he shook hands all around, and made a speech. He was ready for peace, he said. There was no need for more war. He wasn’t sure if he’d go to the reservation anytime soon, however, and he hoped the Oglala could visit and trade at Fort Laramie again, as they had in the more peaceful years of the past. His people had no desire to farm, and as long as there was game, he saw no need for them to learn.

Each side was lost in a dream of the other’s point of view. The whites assumed the buffalo would only last a few more years, and soon the tribes would move peacefully onto the reservation and start farming. The Indians, and especially the Oglala, assumed they had won the war and protected their traditional hunting ground.

Both would turn out to be very, very wrong. Anyone who looked up toward the hill beyond the sutler’s store and the hospital would have seen Mni Akuwin’s coffin still up there, on top of the four-post platform. That view, and the loss it recalled, would have been something both sides understood, if they’d bothered to look.